Knitting Smoke from Garbage

The key to interesting writing is writing it in such a way as to make it interesting.

I’ve been writing a lot lately. In part, because it’s marginally less upsetting than crying. But also because I should probably try to make money again one day. I mean, it’s been what? Like, twenty years? I can’t keep living under this overpass forever.

Anyway, one of the problems that I have with my writing is that I hate it. Which is not ideal for something I’m hoping to inflict upon others. I mean, you don’t have to like it, but I should at least, right? So, I spend a lot of time looking at the stuff I’ve written and shaking my head. I do some frowning, too. Sometimes, I’ll stroke my chin. None of it helps the writing, though. It’s very frustrating.

Eventually, though, I hit upon a solution. And it’s always the same solution. Practically every time. It’s a lesson I’ve learned many times before, and it’s a lesson that I apparently have to learn every single day, and it’s this: Try to make the writing interesting instead of shitty and boring. It’s an odd concept, and I’m not great at it. But even the attempt will get you part way there. Or so I hear.

Here’s British novelist Jim Crace explaining the concept in an article I apparently read twenty fucking years ago (Jesus!)…

[Y]ou must not allow your sentences to be weighed down with unnecessary and unproductive ballast. Every writer has a damaging idiosyncrasy, and that is yours. You remind me of a young author I met when I was an Arts Council writer-in-residence many years ago. She'd written a strong and heartfelt story about the ugly break-up of an appalling marriage, but she, too, was overfond of stating the bleeding obvious. ("The black and white magpies flew across the countryside" was one of hers. Black and white, indeed. The countryside!) As evidence that the warring couple in her story could hardly bear each other's company, she had described how the husband would always find some excuse to escape into the garden, to do a bit of weeding, perhaps, to mow the lawn, to tidy the shed, to burn some weeds, instead of bickering with his wife. "In the last months of their marriage, there was always a bonfire at the bottom of the garden, emitting smoke," she wrote.

A tender image, don't you think? But hardly a rigorous or revealing one. Lazy writing. A bonfire emitting yogurt, or black and white magpies, would have been more engaging for the reader, even if a little silly. Engaging the reader is the essence of good writing, I suggested, and gave the example of a testing metaphor from a book I was reading at the time, Logan Pearsall Smith's Trivia. It required some sophisticated responses from the reader before its meaning could be appreciated. Smith wrote about "that Stonehenge circle of elderly disapproving Faces - Faces of the Uncles and Schoolmasters and Tutors who frowned on my youth", requiring me to conflate those two sets of cold, fixed, stony expressions. I would never be able to see an uncle or a megalith in the same way again. That's literature.

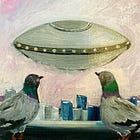

I challenged the woman to make some small changes, to engage the reader in a testing metaphor of her own. Her change was minuscule - only two letters - but that change transformed the sentence from a lazy one to one that was demanding. Instead of "a bonfire emitting smoke", she had written, "In the last months of their marriage, there was always a bonfire at the bottom of the garden, knitting smoke." Her image did not have to be explained. We could see the blackened sticks and branches crossed like thick needles in the nest of the bonfire and the long, grey scarf of smoke that they produced.

Hopefully, this advice helps you knit more smoke that I have in the past two decades.